Experts warn of rising hidden hunger in Nairobi households

A Nairobi mother’s story highlights hidden hunger, where families eat enough to feel full but lack vital nutrients, raising risks of anaemia, poor growth and obesity as food costs and urban diets shift.

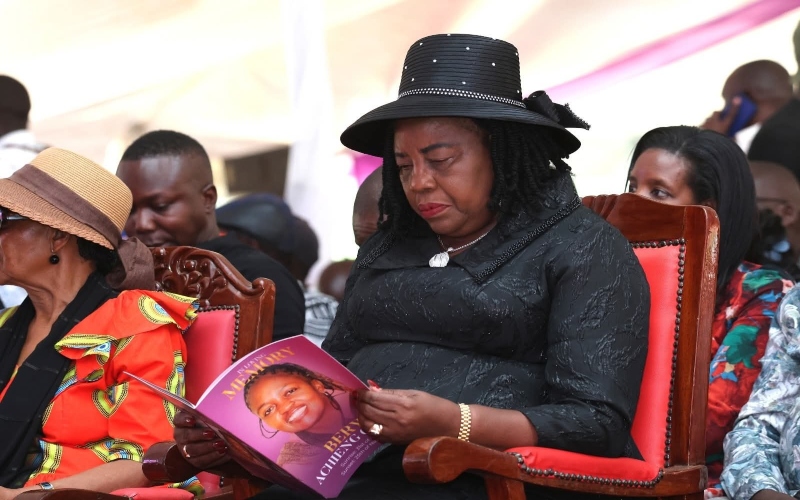

For Sheila Mkonyi, a mother of two and a vegetable vendor in Eastleigh, the daily struggle to balance work and parenting often dictates what her family eats. Her days begin before sunrise and stretch late into the night, leaving her with little time or financial room to prepare nutritious meals.

Like many Nairobi residents, Mkonyi’s eating habits are shaped by her upbringing, where meals mostly consisted of ugali and greens, rice and beans, and the occasional fruit when money allowed. Today, she still follows the same pattern, guided largely by affordability rather than nutrition.

More To Read

- Report finds added sugar in Nestlé baby cereals across Africa

- Study shows women under 50 face higher risk of colon growths from ultra-processed foods

- Nairobi County issues public health alert as heavy rains trigger flooding, contamination fears

- Sweet but dangerous: How junk food hooks kids’ brains and fuels lifelong cravings

- Nairobi clinical officers to stage mass protests, accuse Sakaja administration of ignoring grievances

- Strained, stalled and sinking: The harsh reality at Mama Lucy Kibaki Hospital

“Sometimes, as long as the children don’t sleep on an empty stomach, that’s what matters most,” she says. “I try my best, but we eat what my pocket allows at that moment, maybe ugali and greens, sometimes some protein, githeri, or on other days noodles or French fries. Whatever is available."

For now, even nutritious options like legumes still fall short of what she considers a truly balanced meal, and what her family eats is guided more by what is available than by what is ideal. Though legumes are healthy, they remain the option she settles for rather than the fuller, more varied meals she wishes she could provide.

“I don’t have a meal plan,” she admits. “I go with what I can afford as we trust God for a better day.”

A plate of French fries. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

A plate of French fries. (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Her experience reflects the growing trend of hidden hunger in Nairobi, where households consume enough calories to feel full but lack the essential nutrients needed to stay healthy. Meals dominated by cheap staples such as ugali, French fries, mandazi, and sugary tea create a sense of satiety while quietly depriving the body of vital vitamins and minerals.

Health experts warn that this silent form of malnutrition is spreading as climate change continues to push up the cost of vegetables, milk, and protein-rich foods. With nutritious foods becoming increasingly unaffordable, many families are turning to inexpensive, calorie-dense alternatives.

This nutrient-poor diet puts families at risk of weakened immunity, anaemia, poor child growth, and rising obesity, particularly among women and children.

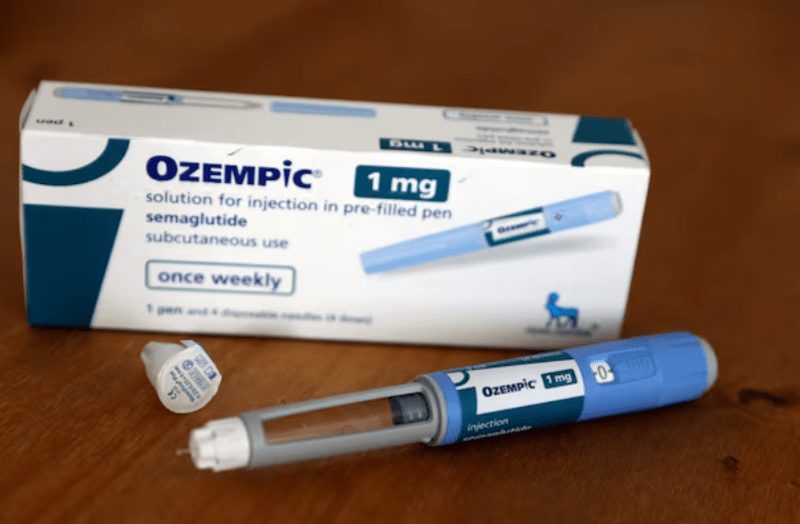

Hidden hunger is a form of malnutrition that occurs when a person’s diet provides enough calories to prevent hunger but lacks essential micronutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, needed for proper growth, development, and overall health.

Unlike overt hunger, which is obvious because a person feels hungry or underweight, hidden hunger can go unnoticed while still causing serious health problems, including weakened immunity, stunted growth in children, poor cognitive development, and increased risk of chronic diseases.

Dr Christine Chege, a senior scientist with the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), points out that even a plate that looks full can be nutritionally inadequate, providing calories but lacking the essential nutrients the body requires.

Dr Chege explains that a healthy plate must be diverse, colourful, and balanced, including not only energy-giving foods but also greens, vitamins, and fruits, not just vegetables or foods that provide calories.

Nutritious food, she notes, provides both macronutrients, like carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, and micronutrients, such as vitamins and minerals. A balanced diet must include a variety of foods, different in colour and category, to supply the full range of nutrients.

Christine Chege, Senior Scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Christine Chege, Senior Scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). (Photo: Charity Kilei)

For example, a meal could include ugali or rice for energy, beans or fish for protein, greens and carrots for vitamins, and fruits like mango or papaya for additional micronutrients. “A meal of ugali and vegetables alone is not diverse enough. Food should come from different categories.”

Dr Chege observes that dietary trends in urban areas are shifting, with more people moving toward processed foods. In the past, many avoided traditional meals, believing processed foods signalled higher social status, a trend she considers concerning.

“Ultra-processed foods are those that have been heavily processed, and in the process, they lose most of their nutrients. What remains are mostly calories, while essential nutrients like vitamin A and zinc are stripped away”.

The researcher highlights that rates of overweight and obesity are rising, especially among women and children. This is linked to poor diets and rapid urbanisation. “If we give our population the right information,” she says, “they can make the right choices.”

She encourages urban households to adopt small-scale food production, such as home or balcony gardens, “Small spaces should not be a barrier to consuming nutritious food.”

Kenya faces a triple burden of malnutrition: Some people are undernourished and lack essential nutrients, others suffer from overnutrition and obesity, and many experience micronutrient deficiencies.

According to Dr Chege, these issues can coexist within the same household, such as an overweight mother, an undernourished child, and another with a micronutrient deficiency. Some children face protein and even calorie deficiencies.

“We’re not saying people should stop eating certain foods entirely; everything should be consumed in moderation, with balance and diversity to avoid moving from undernutrition to obesity.”

According to Wanjiru Kamau, Regional Managing Director at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, healthy and nutritious food begins with nutrient-rich soil.

Kamau explained that if the soil is weak or depleted, the food grown from it will also lack essential nutrients, which directly affects the health of the people who consume it.

Wanjiru Kamau, Regional Managing Director at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). (Photo: Charity Kilei)

Wanjiru Kamau, Regional Managing Director at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). (Photo: Charity Kilei)

She emphasised that the Alliance’s broader work addresses several interconnected challenges, including nutrition, climate change adaptation, agricultural production, and biodiversity.

The organisation works closely with farmers to improve soil health through sustainable practices, recognising that stronger soil leads to more nutrient-dense crops. “Drought is natural,” she notes, “but people dying of famine is not - and it’s something we can address.”

By nurturing the soil, they aim to boost the nutritional quality of the food produced.

However, Kamau stressed that even after nutrient-rich food is grown and transported to markets, significant amounts are still wasted. Tackling food loss is essential to ensure that the nutrients in the food end up on plates, not in dumpsites like Dandora.

"We need to turn nutrients into food, or manure, and capture their value. We must start thinking of food waste as a crime.”

Micronutrient deficiencies remain widespread in Kenya; as a result, many children and pregnant women suffer from anaemia, as well as deficiencies in vitamin A, zinc, and other essential nutrients.

In 2025, obesity overtook underweight as the more common form of malnutrition, affecting approximately 1 in 10 school-aged children and adolescents, around 188 million globally, putting them at increased risk of life-threatening diseases, according to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

The barrier to good nutrition is not the lack of food itself, but the lack of nutrients in the food people consume. Currently, about 50 per cent of what is produced goes to waste, representing a huge loss of nutrition and a missed opportunity to feed the nation healthily.

Top Stories Today